While on vacation in France recently, I had the fortune to visit a few of the world’s leading museums, both in terms of the art displayed and the incredible quality of the exhibit design itself. Museums serve different roles for different people – as tourist destinations, research institution, and entertainment complexes. The spatial complexity of these environments usually makes it possible for individual visitors to carry on completely different agendas, from the die-hard tourist who came to get a snapshot of a masterpiece to the practicing oil painter who spends hours copying a virtually unknown piece. Recently, however, every sizable museum has begun to offer digitally mediated tours meant to accompany one specific type of itinerary, a historical/curatorial tour targeted at a novice audience. This is often available as an audioguide, in the form of a telephone handset that is constantly held to one ear or, more recently, a digital audio player with headphones. Audioguides offer significant advantages for tourists and novices visiting a site: they provide multi-lingual informative tours in a private manner through a non-disruptive audio modality. On the other hand, they can reduce the variety of experiences possible in the museum. To limit the length of the tour, audioguides target only the most well-known details of a collection, leading to a leming-like behavior on the part of the museumgoers. Very experienced or inexperienced visitors stand to gain very little from an audioguide. And, like headphones in general, audioguides promote solitary museum visits, neglecting much of the interpretation and debate that could be fostered when a group of people shares the same space and interests.

Audioguide visitors at Casa Batllo in Barcelona

Audioguide family at Chenonceau

Just as digital audio players have evolved into little tiny movie screens, it would seem that the natural evolution of audioguides should be portable multimedia guides that couple images and videos to audio narration. The Louvre makes available PDA-style multimedia museum guides, hung from the neck by a lanyard and navigated using a touch screen and a tiny stylus. These new devices expand the breadth and depth of audioguides; they contain information on a greater number of artworks and the type of information now includes text, photos, drawings and videos. On the other hand, they are bulky, requiring both hands, eyes and ears to operate; they are confusing to the young and the old; they remain socially isolating (except when seeking help to operate them); but most importantly they distract visitors from gazing at the artwork itself with a tiny, low-resolution screen depicting information widely available in the public domain.

Dad untangles a multimedia guide while Son sneaks a peek at the ‘Victory of Samothrace’

Mom helps Daughter understand the multimedia guide interface

Buying a digital tour is becoming an important part of the museum visit experience and no doubt enriches for some what could otherwise be a confusing or overwhelming experience. There are a number of other types of didactic interaction that are currently possible or could be imagined, to augment the value and richness of a museum visit without the narrowness or social isolation of current techniques. Let me start with what I believe to be the best technique for appreciating artwork, the one that was taught to me as part of an art history and visual art education. Drawing in the museum is a long-standing rite of passage for art students because it serves the double role of teaching an appreciation for art and practicing the craft of drawing. Unlike the typical museum visit, drawing calls for concentrated attention on a single work of art for an extended period of time. In exchange, it makes the visitor intimately aware of the artist’s intentions and the nuances of the artwork. While it may seem like an expert activity, some of the people who benefit the most from drawing in the museum are children. While we may not always have the time to draw in the museum, perhaps interfaces that utilize the same kind of concentrated attention to artwork could be developed to engross rather than distract museumgoers from the art before them.

The two phases of drawing in the museum: looking intently and copying. Plus, you get a souvenir.

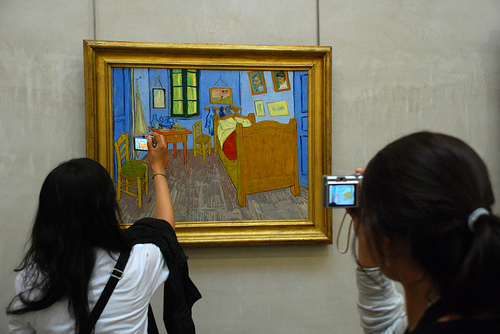

But let’s face it – not everyone has time or cares about individual artworks enough to draw them. Instead, every tourist in Paris seems to have a little digital camera with which they must photograph the Mona Lisa. Why? To prove that they saw it, or, more likely, to see it at all, since the barricade that protects the diminutive tableau forces most people to see it from several meters away. It’s not the best way to interact with art, but it is more than intuitive – people seem driven to do it. Sometimes, tourists take pictures of only a detail of a painting. I often wonder if they ever look at the painting, or if they are merely looking at the pixelated version on the back of their canons. Maybe this too could serve as a gateway to engaging further research and attention to detail, or the cameras could themselves become guides of a sort, adding narration to the individual visitor’s shutter clicks.

The digital camera as microscope in the Musee d’Orsay

Whether drawing or photographing in the museum, being an artist in the museum can bring unexpected perspective to the art on exhibit. But these remain solitary activities, which is why tangible physical kiosks – none of which were used in the museums I visited – are sometimes the most engaging. I wrote a long time ago about the Digital Michelangelo project, an effort to produce a detailed virtual model of the David so that we could see it from new perspectives. They installed a kiosk next to the masterpiece, and it is always packed with visitors who, having seen the real thing, want to zoom in on it, rotate it, see it in a different light – all in an effort to better understand it. The interface is on a large screen with simple tactile controls, so everyone participates in the discovery. At once engaging and collaborative, this is perhaps the best example of an interface that does not sacrifice the ability of each individual museumgoer to discover something unique and to interpret it in the community of the gallery.

2 Trackbacks

[…] designer leonardo bonanni recently went on vacation, visiting some of the top museums in europe. on his travels he realized […]

[…] not generally a fan of audio guides, especially when they cost money. They are free at the MoMA, on the other hand, but they […]